Main content

Top content

Networks and digital economies

Experimente zum Thema

- Networks without managers

- Networks with managers

Hinweis Glossar:

Some terms are explained in our glossary

(in progress)

Networks and network effects

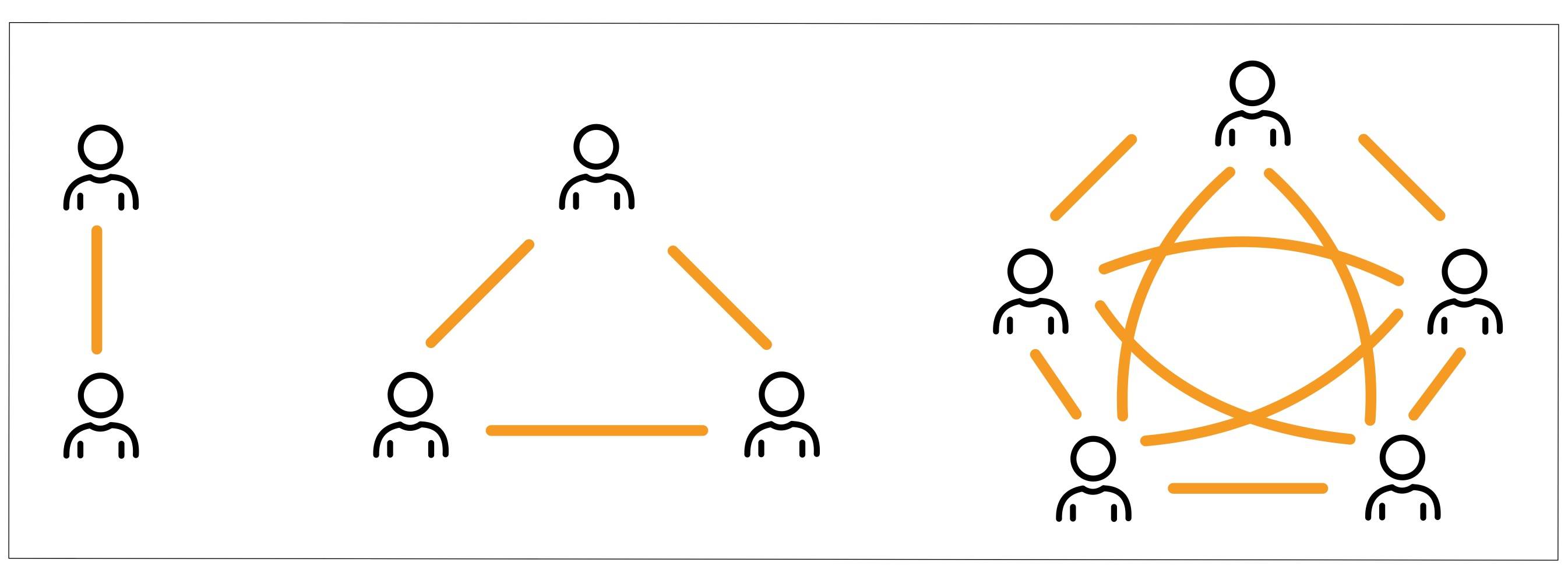

Social networks connect people with each other, technical networks connect telephones, radio stations and radios, computers, machines or sensors. From an economic perspective, networks are special because so-called network effects (also known as network externalities) arise within them. A network effect is created by the connections between the actors in the network. The illustration shows three networks with two, three and five actors. All of them are interconnected. With only two actors there is only one connection, with three actors there are three connections and with five actors there are already ten connections.

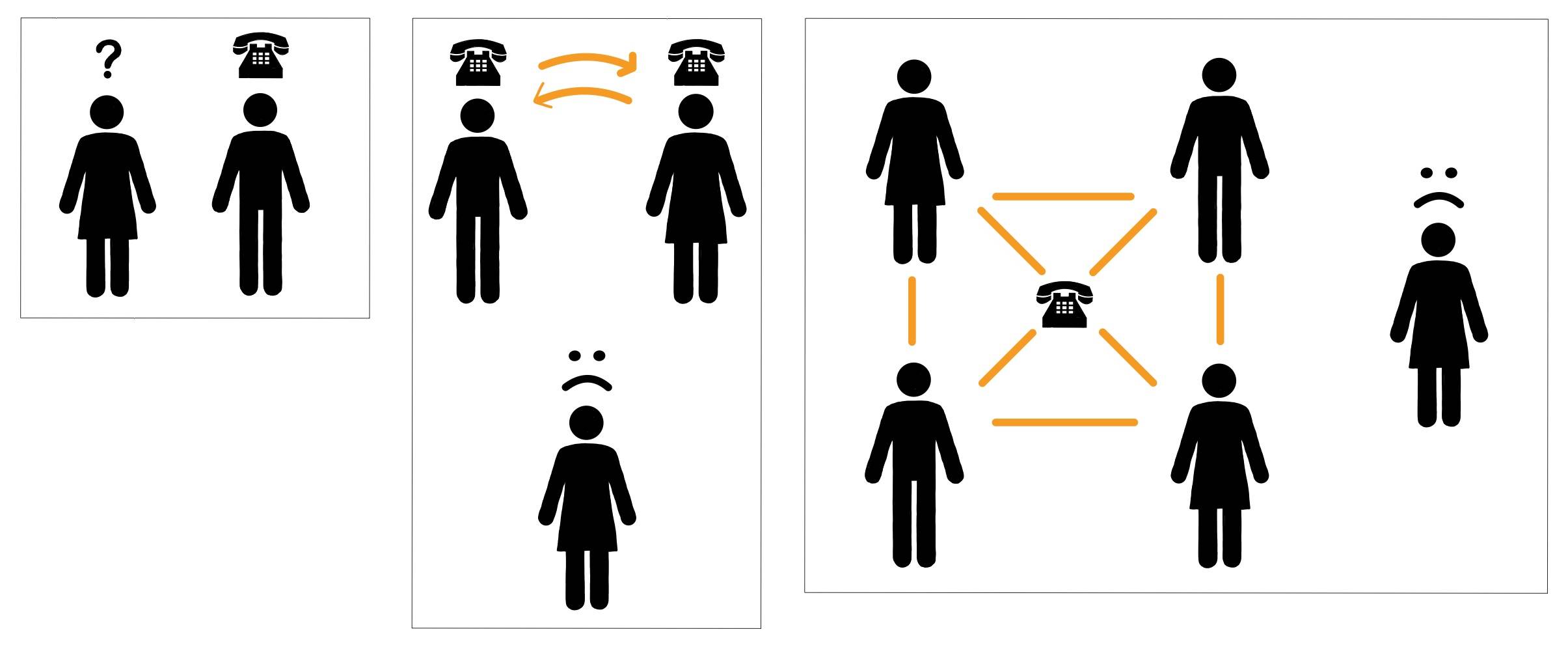

Let's imagine we are talking about a communication network: the players can make phone calls, send text or voice messages to each other via the network. The network effect then consists of the fact that the benefit of all actors in the network increases as the network grows: the more actors there are in the network, the better it is for each individual. The best-known example of this is the telephone: nothing is more difficult than selling the first telephone (what are you supposed to do with it?), the second one is a little easier (you can call someone), and with the hundredth telephone you don't have to explain the benefits any further. The effect is exponential, i.e. the benefit increases disproportionately as the network grows.

A network effect can be positive, but also negative. In this case, the benefit for the individual actor does not increase when the network becomes larger, but decreases. One example of this is transport routes: the more households are connected to a road network, the more people can meet each other, but the more people use the road network, the more likely it is that traffic jams will occur. At some point, the number of users is so high that the road network is overloaded and the benefit for everyone decreases.

The ability of the actors to communicate illustrates network effects, but such effects also exist with physical goods. This is because network effects can not only be direct, as in the telephone example, but also indirect. For example, powerful graphics cards in computers become more valuable if there are more computer games with high graphics requirements, and conversely, the utility of games increases with technical progress in graphics cards. The network effect here exists between two different product groups, software and hardware. However, such indirect network effects also exist for many other goods. Examples include razors and matching blades, printers and toner or coffee capsule machines and capsules.

In the basic version, the experiment on network effects depicts direct network effects, albeit in an abstract and (admittedly) peculiar way: The participants are divided into groups and given the task of solving mental arithmetic problems (what is 9 * 11?). Each correctly solved task scores one point, not only for the participant herself, but for all participants in the group. This creates a network effect: The more people in the group, the more points each individual group member collects!

Digital economies

On the one hand, the term digital economies refers to parts of the economic world in which computer technologies determine the goods traded. On the other hand, it refers to the change in the economic world brought about by computer technologies.

Digital economies differ from ‘classic’ economies because traditional assumptions about how companies produce and consumers buy are no longer correct. A few examples: Uber, the world's largest taxi company, does not own a single taxi; Facebook (or Meta), the largest owner of media content, does not create any (significant) content itself; Alibaba, one of the world's top-selling retail companies, has no warehouse; and Airbnb, the world's largest provider of accommodation, does not own any real estate.

Digital economies are no longer the future of economic life, but already the present, as economic life today is already determined by the countless online connections between people, companies and devices via the internet. This is why information and communication technologies play a central role, and why network effects, both direct and indirect, generally occur in digital economies.

Competition in markets with network effects

We look at the market for digital goods and want to find out what distinguishes this market from the traditional goods market. Digital goods consist of code, zeros and ones. In order to be able to use them, you need adequate information processing of these zeros and ones, which is why digital goods are always complementary goods, i.e. goods that require other goods (computers) in order to be used. Example: A PDF file is only useful if you also have a PDF reader and a computer on which the PDF reader can be installed.

As explained, direct and indirect network effects arise on markets for digital goods. Both determine not only the benefits for consumers, but also the market strategies of the supplying companies.

Let's take another look at the example of the telephone and imagine ourselves back in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, several inventors were working on a new technology at the same time: the telephone. Philipp Reis from Germany invented the first apparatus for transmitting speech and called it the telephone in 1861. At almost the same time, Italian-born Antonio Meucci was working on the same technology in the USA. It was another 15 years before the first practical apparatus was built, and in 1876 it was Alexander Graham Bell who filed a patent application for the telephone (Bell later founded the Bell Telephone Company, now AT&T). So there were several inventors working on a new technology at the same time. This has often happened throughout history, so it is not surprising that after the invention of a new technology, several companies emerge that commercialise different versions of the same invention.

These companies recognise the market potential of the invention, in our example the telephone. Initially, however, only a small proportion of consumers will decide to buy a phone because the benefits are initially small and the technology is still unknown. However, these first customers spread information about the benefits of the new product and the market for it grows thanks to their positive feedback.

At the end of this initial phase of the market's development, a critical mass is reached, i.e. a number of users of the good at which the benefit of the good becomes immediately clear to everyone else. Buying the good (i.e. the telephone) then becomes attractive for all demanders, and those who can afford it buy it. The market for the phone enters its second phase, the boom phase, in which the number of users increases very quickly. At the end of the boom phase, the market is saturated, i.e. many customers have the phone and only a few new customers are added (saturation phase).

The winner takes it all

Even before the critical mass is reached and the boom phase of the market begins, more companies will enter the market, anticipating market developments. The competition between companies is extreme, because in markets with network effects there is a principle: the winner takes it all. This is due to network effects and can be well illustrated by the telephone: let's imagine that there are several companies offering the telephone. All of these providers have to network the devices that they install at customers' premises. If there is no public network, each company must therefore set up its own network.

This leads to competition between the networks, and because of the network effects, the network that grows the fastest wins in this competition. However, customers will observe which network is how big, and new customers will join the largest network - again because of the network effects. This leads to an increasing concentration of customers on just one or very few providers: The winner(s) take(s) them all.

The phenomenon of ‘the winner takes it all’ also occurs in the experiment. This is because the game runs over several rounds and the participants have the opportunity to switch to a different group after each round. Those who want to score a lot of points therefore join the group that already has good mental calculators and as many of them as possible. This concentrates the participants in just one or two groups. Incidentally, good mental calculators could be referred to as ‘influencers’ in the game, as they are the ones who attract other participants.

Examples of the winners of dynamic competition in digital markets are Google in the internet search engine and smartphone operating systems (Android) and Microsoft in the operating systems for PCs. An example of several similarly large winners can be found in the market for games consoles (Sony with the PlayStation, Microsoft with the Xbox, Nintendo with Switch/Wii). If there is only one winner of the competition, this does not necessarily have to be the provider with the best product, as the growth of the network is not only determined by the quality of the product, but also by other, sometimes random factors.

The market dynamics described above also apply to goods with indirect network effects. The only difference to the telephone example is that in the initial phase it is also decided which complementary goods will prevail. In most cases, one of the necessary complementary goods already exists. The computer games industry is a good example of this: which games consoles become established on the market depends very much on which games are available for the respective consoles.

Pricing strategies for customer loyalty

If there is the dynamic competition between providers described above, it is obvious that the providers' aim is to retain as many customers as possible in the initial phase. This can be achieved through the product itself if the company is clearly superior to the competition in terms of technology or design. However, companies will adapt their pricing strategy in particular to the dynamics of the competition: in order to win as many customers as possible, companies will initially only charge very low prices. In extreme cases, they will initially give the product away. In the case of indirect network effects, this can even be a permanent strategy: The manufacturer then ‘gives away’ the main product (the printer, the coffee capsule machine), i.e. offers it at a very low price, and then makes its profits with the complementary product (toner, capsules).

(picture still missing)

However, purely digital products in particular, where the network effect is direct, are often given away and users only ‘pay’ for them by putting up with adverts or using their personal data. YouTube, for example, has only had the premium function in Germany since 2018, where users can pay money to watch videos ad-free.

The strategy of offering the product very cheaply in the initial phase, or even giving it away, is successful if it enables your own network to grow quickly. However, the same network effects that encourage customers to join the network also make it difficult for the same customers to leave the network again, because if they leave the network, they lose their contacts and have to rebuild them in the other network. The customers are ‘locked in’.

(picture still missing)

Providers can take advantage of this locked-in effect by increasing prices later on. The locked-in effect is also present in indirect network effects and is even particularly evident there: for example, anyone who has opted for a particular model of games console can only choose from the range of games available for this console, and this gives providers greater scope to charge higher prices for the games.

In order to understand the price strategies on markets with network effects, there is a variant of the network game with ‘group owners’. In this variant, there are also several groups, the participants continue to collect points for their group by solving mental arithmetic problems, and they can continue to change groups after each round. Now, however, there are also group owners who take on the role of entrepreneurs. The group owners set a price before each round, which in the game corresponds to a membership fee for the next round. Owners can set this price to zero, in which case membership of the group is free. However, the owners can change the price over the rounds.

Links and Downloads

Here you will find our glossary

You can obtain the appropriate student text here.

Click here for the experiments

Here you will find materials for further discussion

Here you will find the literatur